Film handbills were produced by distributors, producers, or owners of the projection rooms. A single film could have several designs of handbills, sometimes due to a replenishment made after the release of the film. They were mainly used between the 1920s and the 1960s and served as a form of advertisement distributed in cinema box offices. Over the years, film handbills have become collector’s items.

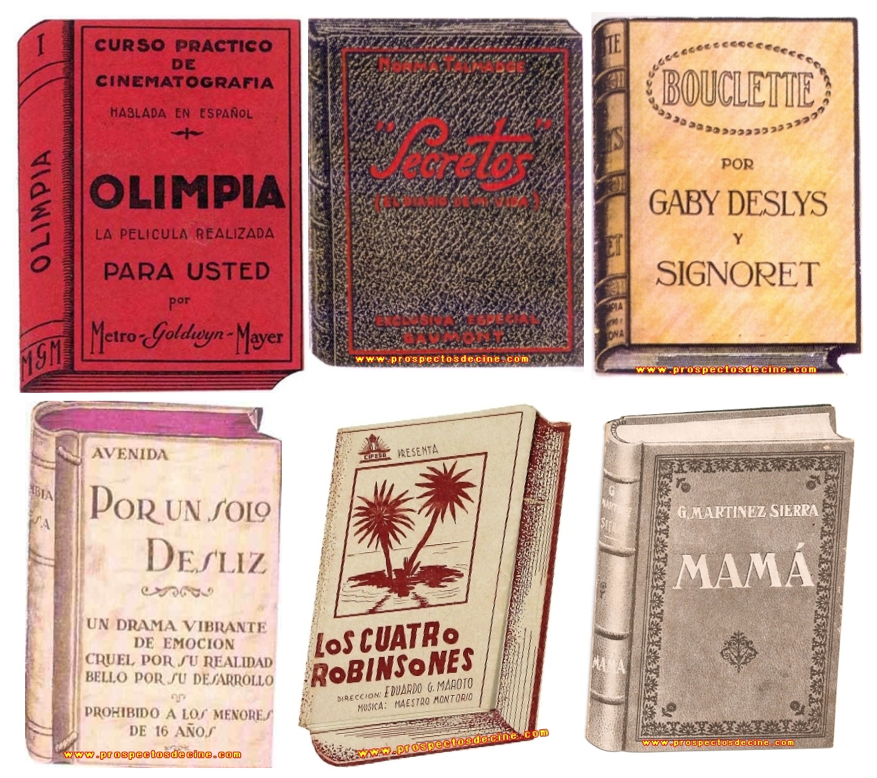

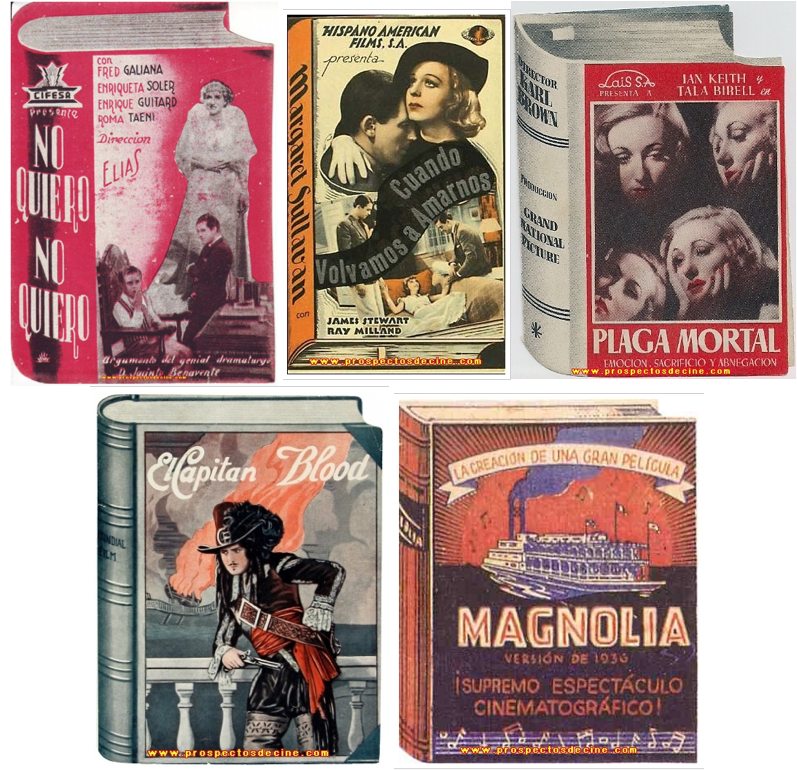

The most dominant format is a rectangular sheet with dimensions of 13,5 x 8.5 cm and a cover that included the film’s poster. Among all the possible styles of film handbills, we have the die cut designs, where the shape of the handbill is closely related to the theme of the film. This format enjoyed a wider creative freedom than the other styles of programme handouts and was popular due to its uniqueness.

Die cut handbills feature more creative designs with unique forms, increasing the value of the program due to its particularity. Some shapes, such as books, guns, hearts or planes, are often repeated, leading to a typology of forms. These forms mentioned before are the most dominant, but there are many others like busts, silhouettes of the main characters, animals, shoes, huts, train tickets, etc.

“Olimpia” (Jaques Feyder. EE.UU., 1930); “Secrets” (EE.UU., 1924) 20,5 x 13,3 cm.; “ Bouclette” (France, 1918) 1,8 x 10,7 cm.; “Damaged Lives” (EE.UU., 1933) 19,7 x 14,6 cm.; “Los cuatro robinsones” (Spain, 1939); “Mamá” (EE.UU., 1931) 25 x 17,4 cm.

“No quiero, no quiero” (Spain, 1939); “Next time we love” (EE.UU., 1936) 20,3 x 16,2 cm.; “White Legion” (EE.UU., 1936) 15 x 10,25 cm.; “Captain Blood” (EE.UU., 1924); “Magnolia (EE.UU., 1936) 14,3 x 8.7 cm.

“La justicia del Coyote” (Mexico, 1956) 17,7 x 9,8 cm.; “El hombre de la diligencia” (Spain, 1964) 23 x 9:50 cm.; “Colt 45” (EE.UU., 1950)

“Brigada criminal” (Spain, 1950) 17,8 x 12,1 cm.; “Billinger” (EE.UU., 1945)

Top part: Back and front of “Escuadrilla (Spain, 1941) 16 x 16 cm.; Bottom part: “Alas de juventud” (Spain, 1949)

“El amado bárbaro” (1924); “Es hora de amarnos” (1933) 13,1 x 12,2 cm.; “Love me tonight” (EE.UU., 1932) 17,8 x 9,5 CM.; “Una semana de felicidad” (Spain, 1934)

In the larger context of film handbills, die cuts designs make up a minimal percentage. However, due to its scarcity and uniqueness, they are of greater interest. This article provides a small sample of recurring shapes throughout time, likely due to their past success capturing the interest of viewers and their association with certain cinematic genres.

All the images seen in the article have been obtained from the website«Prospectos de cine de Paco Moncho», which has kindly allowed us to use them for this article.

Translated by:

Ramón Humberto Ramos Martín

Ramón Humberto earned a degree in Modern Languages and theis Literatures at UCM, specialising in German as his major and English as his minor. After spending a year working as Spanish assistant in two highschools of Vienna, he is currently enrolled in a Master’s program focused on English Teaching at UDIMA.

Author:

Diana Ramos

Content editor

Diana Ramos earned a Bachelor’s degree in History, a degree in History of Art and a Master’s in Document Management, Libraries, and Archives.

Her academic background is complemented by her professional experience in national and international libraries.

Since 2017, she has managed the library of the AISGE Foundation.