During the Long Depression of the 1870s, a man named Edward Owens took up piracy in Chesapeake Bay. He had run out of money, his work as an oyster fisherman no longer able to support him. Born in Virginia in 1853, he chose Watt’s Island as the location for his new profession after hearing about its past of harbouring pirates. Thanks to research by student Jane Browning, Owens subsequently became known as the last American pirate. Posting her research on a blog of the same name, it was described as an ‘example of the power of these tools for an individual to track and frame their own educational experience’ and was reported on media outlets including USAToday.com. On Browning’s blog, you can view photographs of items from archives including Owens’ will and follow links to watch a Youtube video of her visiting his abandoned home and gravesite.

Except Edward Owens never existed. The whole thing was a hoax created by a group of students at George Mason University. The brainchild of Professor Mills Kelly in the Department of History and Art History, Kelly taught the students a course titled ‘Lying about the Past’ in 2008. The syllabus stated ‘we’ll make up our own hoax and turn it loose on the Internet to see if we can fool anyone.’ Through creating and learning about historical hoaxes, Kelly’s aim was for his students to become ‘better consumers of historical information’, making sure they were acquired with the tools to think critically about sources they came across in their research.

The classes’ result was successfully deceptive and only revealed as a hoax once media outlets began reporting it as factual. The smoke screen of authenticity was propped up by bad quality photos down to ‘kind of old’ digital cameras and convenient claims of broken photocopy machines with transcripts for substitutes. In some cases, documents from archives were merely set in a new context within Owens’ narrative, masquerading as evidence to back up the story.

The advent of digital technology has allowed increased access to archives, most notably through digitisation projects. Having downloadable images means people can take them, put them in another context or alter them altogether. Old images can become something new and new images can be made to look old and be mistaken for the real thing.

Artist Joan Fontcuberta has explored this throughout his work, challenging ‘disciplines that claim authority to represent the real – botany, topology, any scientific discourse, the media, even religion.’ In his Stranger than Fiction exhibition in 2014 at the Science Museum, his ‘Fauna’ series was presented as a replica natural history exhibition. Purported to be the long-lost archives of German zoologist Dr. Peter Ameisenhaufen, it included photographs, x-rays and taxidermy. None of the animals existed. Each specimen was an amalgamation of different species and had been given a ‘scientific’ name. These included a winged monkey called a ‘Cercopithecus Icarocornu’ and a snake with legs named ‘Solenoglypha polipodida’. Visitors were never warned it was a fabrication.

The result is a disorientated audience. The exhibition glaringly lies to our faces in a place we freely reward with implicit trust. Despite our better judgement, doubt creeps in. Could this be real? In a setting like this it can become worryingly convincing. When the same work was shown at the Barcelona Museum of Natural Science in 1989, 30% of university-educated visitors aged 20 to 30 believed some of the animals could have existed. In the same Museum, Fontcuberta recalls seeing a father slap his child on the back of the head for saying the exhibits were fake. The father’s reasoning? The exhibits were in a museum therefore they must be real. ‘It was interesting to me that the child wasn’t educated in the truth of the museum; he wasn’t perverted by culture. This is a very important political concern.’

Throughout his work, Fontcuberta makes the point that although the amount of pictures we take has increased, it has failed to improve how well we read and perceive images and their context. Having worked as a retoucher I know that everything from models, food, cars and furniture are doctored. With 68% of adults admiting to editing their images before they post them online, altered images are becoming the new normal. What does this mean for digital images of factual and historical documents, objects and art works on the web?

Fontcuberta’s work along with that of the students from George Mason University raises difficult but important questions. When work like this appears, we find it both humorous and horrifying. Throughout our lives we are ‘educated in the truth of the museum’ and persuaded that if it’s been photographed then it exists. The work I’ve referenced here forces us to question this and contemplate the more sinister possibilities. Fontcuberta’s aim is just this and considers his work a ‘vaccine’. ‘My mission is to warn people about the possibility that photography might be doctored and show why people need to be sceptical of images that influence our behaviour and our way of thinking.’ No matter your reaction, they expose weaknesses in ourselves and in the platforms, organisations and projects these images and information are made available from.

How, as online collections continue to increase in size, can museums and archives assure that images of collection items remain uncompromised? Strict digitisation standards and an ethos of capturing everything ‘as is’ contradicts the trend for filters people are applying to their own images. Should we be educating and encouraging people to respect the standards we work to when sharing images online? Online collection use and social media engagement are becoming increasingly relevant to a museum’s or archive’s success. Developing user activity online inevitably means relinquishing some control and allows inventive and brilliant repurposing of archives and museum collections. However, it will become increasingly important to find a balance so that the facts remain clear and digitised items avoid being corrupted while they move through the web.

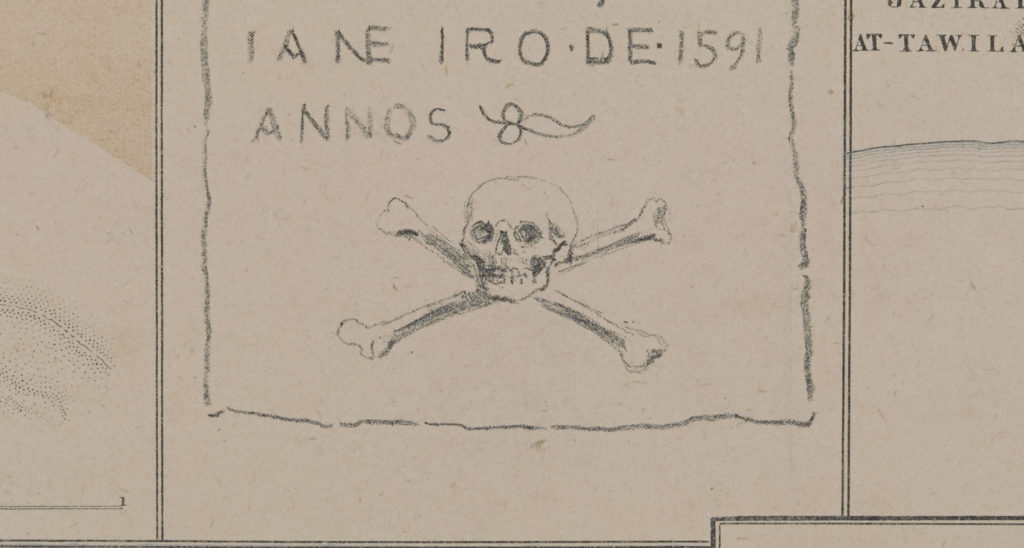

Header image: Historical maps of Hormúz Island, British Library: Map Collections, IOR/X/3127, in Qatar Digital Library <https://www.qdl.qa/archive/81055/vdc_100000006836.0x000001>.

Hannah Negle

Hannah Nagle is an Imaging Technician on the Qatar Foundation Partnership Programme at the British Library. She has previously worked at the Science Museum and the National Archives. Hannah has a BA (Hons) degree in Photography and graduated in 2015.

Article edited by: Noemi Ortega Raventós