In January 2007 I moved from the UK to India to teach in the department of Visual Communication at Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology in Bengaluru. Walking through the city I came across matchboxes almost everywhere I went. At a cost of one rupee, these economical and disposable matchboxes are often found empty and discarded on the roadside near truck stops and littering the footpaths around chai stalls and cigarette shops. Purchased from convenience stores, these ubiquitous objects are commonly used in homes to light stoves, the pious havan or diyas for religious rituals and lighting cigarettes or their cheaper counterparts, the beedis.

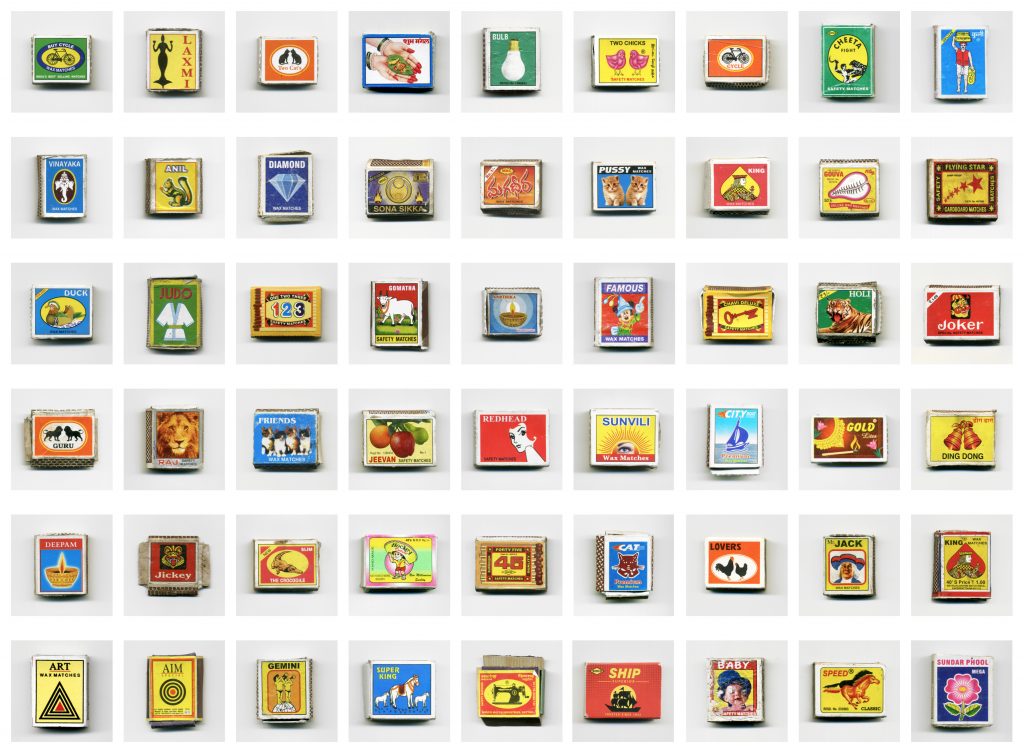

One of the first matchboxes I came across in Bengaluru featured an illustration of a killer whale with the word ‘Dolphin’ written above it. Another early find had a photograph of three ‘Famous’ kittens in a wicker basket. Later I came across a matchbox titled ‘Jamesbond’ with an illustration of a German Shepard. Coming from a background in visual communication and editorial illustration, where the clear communication of messages was central to my practice, I enjoyed the seemingly random relationships between text and image present on so many of these labels. Over time I collected a variety of matchboxes from across India and as the collection grew commonalities between designs began to emerge, with characteristics that include the duplication and mirroring of iconography, incongruous juxtapositions between text and image, thematic variations, textual iterations and copy-cat imitations of popular labels.

No.6, Yelahanka, Bengaluru, 2007

No.44, KB Jacob Road, Fort Kochi, September 2008

No.698, Defence Colony, Indiranagar, Bengaluru, July 2015

No.737, Brigade Road, Bengaluru, December 2016

For me, collecting and categorising these small visual-tactile objects was one way of making sense of my surroundings and the local visual culture that I found myself engaging with. The imagery on these boxes include Hindu symbolism, historical figures, Bollywood actors, foreign brands and cartoon characters, everyday objects, consumer goods, aspirational items, and a variety of popular and exotic animals. The disparate visuals, meanings and juxtapositions that are present through the collection encapsulate quite perfectly the heterogeneous and hybrid visual culture seen in many parts of India today. As cultural artefacts these matchboxes tell us about national identity, modernity and tradition, gender roles, religion and globalisation and how these themes often merge and co-exist.

Phillumeny, the practice of collecting matchbox labels requires commitment and discipline. The routine process involves photographing each design, maintaining a physical and digital archive along with a record of the date and location of where each matchbox was found or purchased. In the essay ’The System of Collecting’, Jean Baudrillard wrote that “it is invariably oneself that one collects” (1994, p. 12) and as visual signifiers, many of these designs embody personal memories. Collectively the visible scars of the battered boxes tell a story, mapping the places I have been to and the experiences I have had… an early morning trek through Periyar National Park with my father and brother, a 48-hour train journey to Varanasi with my students, cycling and sunburn in Hampi and many conversations with friends and colleagues in Bengaluru.

No.707, Kruti Saraiya, September 2015

No.160, Yelahanka New Town, Bengaluru, 2009

No.44, KB Jacob Road, Fort Kochi, September 2008

While the visual and material qualities of these matchboxes vary between regions, a large number of them are printed in Sivakasi, a town in Tamil Nadu known for producing fireworks. In the ten years that I lived in India my collection grew to over 750 matchboxes. What has kept me going is that new labels are produced all the time and across such a vast country, as India is, I could only ever have a fraction of the designs available. The collection can never possibly be complete and so each new addition does not offer a resolution, but instead adds to the continuing story. It is the notion of absence which is essential to the act of collecting. Baudrillard wrote, “the collection is never really initiated in order to be completed… the missing item in the collection is in fact an indispensable and positive part of the whole, in so far as this lack is the basis of the subject” (1994, p. 13).

In 2018 my interest in collections led me to the British Library, where I work as a digital imaging technician on the Qatar Foundation Partnership Programme alongside a team of photographers, archivists, content specialists, translators and conservators. The skills I have developed in this role can be applied to my own digital archives. This includes photographing the matchbox collection to higher imaging standards and with due consideration towards image size, resolution, consistent lighting and accurate colour. A lot of visual, textual and material information is currently missing from my digital matchbox archive, including the reverse sides of the boxes, which include details about the price, manufacturer and place of production as well as the phosphorus striker strips on the sides that display a variety of patterns. At the British Library we photograph the front, back, spine, edge, head and tail of each book, similarly, capturing the matchboxes from all six sides will provide information about the physical condition of each item.

In my role at the British Library I have been introduced to principles for conserving, archiving, managing and curating collections and this engagement has provided me with ideas for developing the Indian matchbox project. While the metadata of my archive includes numbering and information of where and when each matchbox was found, this can be expanded to include details of the manufacturer, place of production, label description, box measurements, material and cost. I began digitising Indian matchboxes over ten years ago, with the simple aim of sharing the range of unique designs online via my personal website. My long-term aim is to create a dedicated website for the collection, with high-quality images that are searchable and categorised sequentially and thematically. This may provide contextual information on the design, cultural, historical, social and economic aspects of Indian matchboxes along with personal stories about notable items. All of this shows that while I no longer live in Bengaluru, this project is far from complete and my journey through the collection has a long way to travel.

This Indian matchbox project is about drawing meaning from a personal collection of cultural designs that are individually unique and collectively identifiable. The full collection of ‘Matchboxes for the Subcontinent’ can be viewed on my website.

No.533, Doddaballapur Road, Yelahanka, Bengaluru, April 2012

Bibliography

Baudrillard, J. (1994). The System of Collecting.

Copyright

Images property of © Matt Lee