(Archivoz) Could you outline the negative and positive aspects of reading cataloguing records? For example, do you generally find the descriptions of the records to be comprehensible/accessible/useful?

(Joanne Paul) It really does depend, and the shorter the entry, the more likely it is that I will need to consult the original. Translation is also a potential problem with some catalogue/calendar entries. For an initial search, it is of course useful, and gone are the days when scholars could spend a decade or two on a project, just going through archive boxes to their hearts’ content. In some ways, this is exciting, of course, because it does mean that new discoveries might be around the corner, if people are willing to do the work of checking originals.

(A) And the same question regarding digitally accessible records.

(J P) I’m extremely grateful for digitised records and sources. They’re usually more searchable, more accessible (fees aside), and often allow the document to be manipulated in various ways (zoom in, play with light/contrast, add highlights, notes, etc). Of course, there are caveats to each of these, and for very important sources, I usually like to (a) read the catalogue/calendar entry, (b) get a digitised copy and (c) get hold of the original. It can be helpful, as well, to have a look at what has been archived with it. This isn’t always possible, and it would be extremely expensive and time consuming to do for every document, but this triangulation is worth doing for documents crucial to my research.

(A) For your latest book, The House of Dudley: A New History of Tudor England, you completed your research and writing in the middle of the lockdowns. Can you tell us about this experience, and how you approached this work?

(JP) COVID did make finishing the book difficult, especially as I’m clinically vulnerable. Fortunately, I had done a fair bit of archival research before lockdowns, and the final half of the book moved into a period that had received more secondary coverage. There were some archives I had hoped to explore, but at the end of the day, it might not have been necessary, and sometimes not being able to get to an institution can just save a day’s unnecessary work (and travel). Research is often about rabbit-holes and goose-chases, and while they’re interesting and can turn up fascinating results, especially towards the end of a project they can just be a form of potentially productive procrastination. Still, I am certain that I missed some things, and I look forward to work that develops on mine with more regular archival access.

What I especially found difficult about the limitations of lockdown was the inability to connect, physically, to the past. A lot of scholarly motivation, for me at least, comes from sense of interacting with a past reality both different from a similar to our own, and that is more difficult when you can’t physically interact with sources or locations.

(A) Do you have any “anecdotal” stories from your time researching and writing your book that reflect your interactions and/or relationships with archivists or librarians.

(JP) As I mentioned above, I really valued my time at the College of Arms. Because it is such a small space and they typically only have one researcher in at a time, I was able to work with this archivist much more closely than at, for instance The National Archives. There was a real sense of working together to get to the bottom of the question (in this case, the dates of birth of the children of Jane and John Dudley, which are included in an appendix to the book). I am very grateful to them.

(A) Your books are non-fiction but are written in such a way that any person can read and enjoy them.

(JP) This kind of outstanding research and communication is hugely important as it gives the general public insight and access to realities they cannot otherwise reach. Sometimes, with this kind of publication, people who don’t have experience in the sector cannot see the depth of research that’s involved behind writing, or the difficulties that accompany the need for care and accuracy in the writing. Can you describe your experience in adapting specialist research and knowledge for a general readership?

I appreciate this question very much. There are a lot of misconceptions, I think, about the ‘divide’ between ‘academic’ and ‘public’ or ‘trade’ history, with the suggestion that rigorous research perhaps only belongs in the former (and, conversely, communicating in an engaging way with the public only in the latter!). I actually found I required more research, and especially archival research, in writing House of Dudley than I had for my two books with academic presses. This had a lot to do with the style of writing; because I was keen to furnish ‘scenes’ with full sensory descriptions, I had to – for instance – find out about the furniture! I needed inventories, account books, ambassadorial reports, etc, etc, just in order to describe what the ‘background’ to the scene looked/sounded/smelled like.

The divide that I was, and am, very firm on is that between imagination and invention. Imagination, in my view, is the necessary tool of the historian, no matter their audience. Invention is the necessary tool of the fiction writer. There might be times and places where invention is helpful to a historian writing non-fiction, but these must be carefully sign-posted and justified. I was careful not to invent anything in The House of Dudley. Instead, I was trying to paint a picture of the world as it was, in order to better understand the actions that figures in the past took, and in order to make it interesting to the reader, to transport them. If our objective as historians is to cultivate a better understanding of the past, then the expression of imagination through narrative prose, founded on and supplied by rigorous research, is one of the best means by which we have to accomplish it.

There were, of course, times I had to get creative, not just with the prose but with how I used sources. For instance, there is a letter written by Robert Dudley to William Davison from March 1586, in which Dudley (essentially) throws Davison under the bus, blaming him for all of Dudley’s actions in the Netherlands which have provoked the queen’s rage (BL Harl MS 285, fol. 230). Davison, rightly, objects to this, and has added marginal notes to the original letter, denying the accusations (“denied”, “Let Sir Philip Sidney and others witness”, “All of this makes nothing to the purpose against me”, etc). In order to bring this to life for the reader, I relayed the letter and the response as a dialogue, never claiming that that was how the interaction took place (I described it as above) but transitioning into the style of writing of a conversation. Likewise, when I was dealing with dialogue relayed in a report, I shifted pronouns and tenses in order to relate the scene that the report described, making it more immediate. But all of the dialogue in the book (along with everything else) comes from the sources.

(A) Can you tell us about any of your most recent discoveries in the records?

(JP) I’ve been on a bit of a hunt, lately, for some details about the subject of my next book, particularly details about his early life. It’s taken me to the London Metropolitan Archives as well as the Archives of St George College at Windsor Castle. The archives at St George were reminiscent of my time at the College of Arms, and I was able to work very closely with the archivist. I’m pleased to say there were some very detailed accounts from the school where my subject studied as a boy, which I think will serve me well in writing the next book. I think I will also have some pretty controversial things to say about where this person was born (it’s not where the blue plaque says it is!), thanks to my time at the LMA.

(A) Can you give us any hints about what your next project is?

(JP) At the time of writing, it’s not yet been announced. But its someone who appears, briefly, in House of Dudley, and about whom I’ve written before (I suspect that rather gives it away, but you’ll have to wait for… ahem… more!). In writing this new book, part of my contention is that we’ve spent little time trying to recover details of his life from the archives, so off on many archival goose-chases I go!

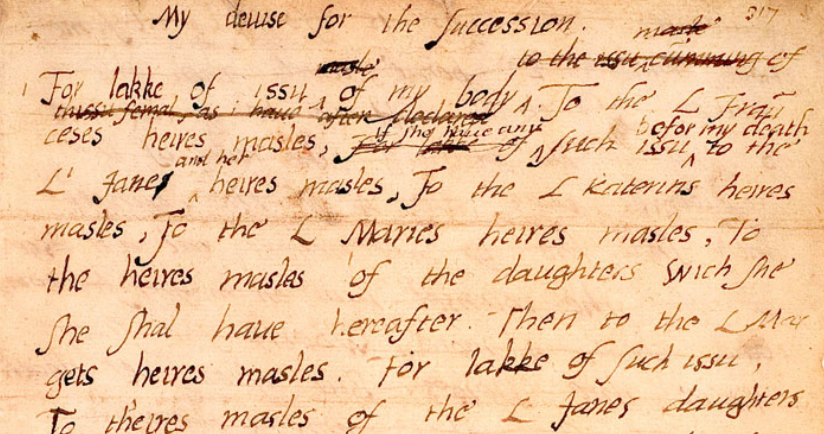

Banner is a fragment of the letter from Edward IV’s “Devise for the Succession” in his own hand. Inner Temple Library, London, Petyt Ms 538 vol 47, f 317.

Robert Dudley Leicester, Public Domain. Wikipedia Commons.

Interviewee:

Joanne Paul

Senior Lecturer in Intellectual History at the University of Sussex and a writer, historian and broadcaster

Joanne Paul is Honorary Senior Lecturer in Intellectual History at the University of Sussex and a writer, historian and broadcaster working on the history of the Renaissance, Tudor and Early Modern Periods. She has written for the Cambridge University Press ‘Ideas in Context’ series, and has been widely praised for her work on Thomas More, William Shakespeare, Machiavelli and Thomas Hobbes.

The House of Dudley is her acclaimed history of the Dudley family. Picked as a Times Book of the Week and Book of 2022, The House of Dudley also garnered excellent reviews in The Telegraph, The Sunday Times, Mail on Sunday, Literary Review, Spectator and was featured in History Today and BBC History Magazine.

Interviewer:

Noemi Ortega Raventos

Global Director, Archivoz Magazine

Noemi is a Content Specialist, Archivist for the Qatar Foundation Partnership Programme at the British Library, Director at Archivoz Magazine and Board Member of SEDIC (Spanish Society for Scientific Documentation and Information). She received her MA in Archives and Records Management from ESAGED/UAB (Graduate School of Archival and Record Management/Autonomous University of Barcelona) in 2014. She holds a BA Degree in History and MA in Medieval Studies from UB (University of Barcelona).